"For any authority, however flexible and however enlightened, must in the last resort of all depend upon respect. In King’s we were all accounted equals but we were equals who respected one another and based our respect in a proper recognition of individual excellence; and so there could be authority between equals. But in the world at large there is no respect. Or rather, there is so much respect, since anything or anybody at all must be accorded it, that the word is made meaningless. The most trivial platitudes, the most misleading and sentimental half-truths, the merest non-sense—all must be received with ‘respect,’ less feelings be hurt and ‘justifiable resentment’ aroused. Is the work shoddy? Are the foundations shallow, the support unseasoned, the bricks carelessly laid? But this, my friend, is the work of free and equal men, and even as the house totters to the ground you must treat the builders with ‘respect.’ Fools, knaves, malingerers; the stupid, the incapable, the idle and the vicious, the spiteful, the envious, the mediocre and the mean—any and all of these you must ‘respect.’ Respect the people, respect their ‘rights,’ respect labour and respect its dignity, respect simplicity, respect ignorance, respect superstitious opinion, public morals, minority prejudice and majority hysteria—all these you must and will respect.

But one thing you may not respect. Excellence or merit. Because if you respect this, you stand to allow that someone is better than someone else, and that, by current reckoning, is to destroy respect. Respect has been inverted: it is now what the great or gifted man must pay to his average fellows—in return for which they may possibly suffer him to serve them.

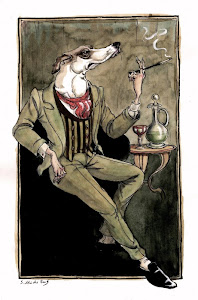

Their respect is reserved for a different purpose—to console and flatter themselves. There can be none to spare for the authority of learning or of practiced tolerance or even of plain fact: still less to spare for that honourable figure of a vanished age—the English Gentleman."

Simon Raven, The English Gentleman (1961)