We live in an overwhelmingly nice age, where a plastic politeness abounds, and where people are afraid to speak their mind for fear of offending others. In such an age, the truth suffers and dishonesty reigns.

I can therefore tolerate a certain degree of rudeness in others. I am referring here to people who speak their mind and converse in an engagingly direct manner. They are a refreshing variation. They are flawed, certainly, but their errors are open to correction. Plus, they can serve as a reminder to the rest of us. I do not of course encourage rude behaviour in any form, but an occasional manifestation here and there is a cost I am willing to pay. What I really can not abide is an

absence of manners in others. People who exhibit a lack of self-knowledge, who are unaware of their deficiencies, who simply don't give a shit, are a bane to society.

A fresh incident has given rise to my thinking, in case you are wondering. I met with my jeweler yesterday to look at a new piece I recently commissioned from the Middle East. I wore a Luciano Barbera lightweight tweed sport coat, a pink dress shirt with spread collar, grey flannels in a 10 oz. weight, and C&J semi-brogues in burnished chestnut. His office was nearly empty. However, as we inspected the piece together and I pretended to know something about jewelery design, a small crowd gathered, among them a plump thirtysomething blonde American woman and her equally chubby mother. The younger woman immediately hurled questions at me: “Is that yours?” "How big is it?" “Who is it for?” “How much did it cost?”

As I fended off the intrusive questioning, she snatched the item from the jeweler’s hand and attempted to try it on. Mere words can not convey the magnitude of my revulsion at that moment, but you may imagine what I was thinking. I seized her wrist and took hold of the piece, telling her, “This is not yours.” The woman looked startled, laughed, and walked away. As they neared the door, the mother approached me and whispered an apology.

They are not alone, of course. This is an area brimming with the self-made rich: celebrities, entrepreneurs, professional athletes. In other words,

nouveau riche. Along with the wealth comes complete self-absorption. Success seems to infect them with a bloated self-regard and a disdain for boundaries, customs, rules, and standards. People mistake informality for friendliness. The lack of reserve, presumptuousness, and over-familiarity are infuriating.

The only solution in these situations, I have determined, is to shore up a Hadrian's Wall of coldness and detachment, to keep the barbarians at bay, while adopting a more resolute policy with the ones who somehow make it through. At the same time, taking a cue from nature, it might make good sense to sport more distinct clothing, including bolder emblematic ties and more colourful madras shirts, as if to say:

approach with caution. I will let you know how it all works out.

A troubled career as a schoolboy may for some be cause for shame, but for me it opened up an unimagined world. Following my expulsion from school due to my involvement in what later became known as the Mayonnaise Affair (about which I have written elsewhere), it was decided I would complete my studies with a private tutor. Mr. Regelous was an ex-Jesuit priest from South Africa who specialised in the academic rehabilitation of wayward boys from the Catholic public schools.

A troubled career as a schoolboy may for some be cause for shame, but for me it opened up an unimagined world. Following my expulsion from school due to my involvement in what later became known as the Mayonnaise Affair (about which I have written elsewhere), it was decided I would complete my studies with a private tutor. Mr. Regelous was an ex-Jesuit priest from South Africa who specialised in the academic rehabilitation of wayward boys from the Catholic public schools.  Mr. Regelous was a large, blonde-haired chap with a broken nose and the physique of a rugby player, which, considering he played at school and at university, made perfect sense. After coming down from Oxford (Campion Hall) he had spent a few years on assignment in Rhodesia. His duties gave him enough time for other pursuits, including an interest in native wildlife. Mr. Regelous became somewhat of an expert on reptiles, I later discovered, and his detailed observations of the Cape Cobra (Naja nivea) in Southern Africa were published in the scientific journals of the British Herpetological Society. The rigors of ministry and missionary work, however, eventually alienated him from priestly life. He returned to England and took up tutoring.

Mr. Regelous was a large, blonde-haired chap with a broken nose and the physique of a rugby player, which, considering he played at school and at university, made perfect sense. After coming down from Oxford (Campion Hall) he had spent a few years on assignment in Rhodesia. His duties gave him enough time for other pursuits, including an interest in native wildlife. Mr. Regelous became somewhat of an expert on reptiles, I later discovered, and his detailed observations of the Cape Cobra (Naja nivea) in Southern Africa were published in the scientific journals of the British Herpetological Society. The rigors of ministry and missionary work, however, eventually alienated him from priestly life. He returned to England and took up tutoring. Based at Marlow, Mr. Regelous had under his guidance several boys in the area. He followed a traditional curriculum with a focus on the Classics. I thrived in his care. Studying under him ignited a lifelong affinity for the works of Thucidydes and Xenophon, amongst others, writers that still bring me delight in the quieter moments. English poetry was another area where Mr. Regelous excelled, and he introduced me to minor poets with whom I was unfamiliar. I was encouraged to commit my favourite works to memory. Even today I can still recite on demand large chunks of Byron, Brooke, and Donne ('Seal then this bill of my divorce to all/On whom those fainter beams of love did fall...').

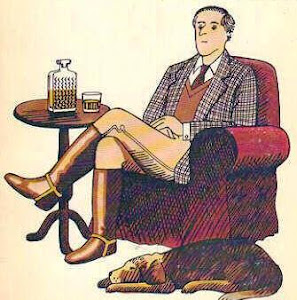

Based at Marlow, Mr. Regelous had under his guidance several boys in the area. He followed a traditional curriculum with a focus on the Classics. I thrived in his care. Studying under him ignited a lifelong affinity for the works of Thucidydes and Xenophon, amongst others, writers that still bring me delight in the quieter moments. English poetry was another area where Mr. Regelous excelled, and he introduced me to minor poets with whom I was unfamiliar. I was encouraged to commit my favourite works to memory. Even today I can still recite on demand large chunks of Byron, Brooke, and Donne ('Seal then this bill of my divorce to all/On whom those fainter beams of love did fall...').  Mr. Regelous was always well-dressed. His normal attire consisted of an immaculate tweed jacket, checked shirt, knit tie, and flannels or cords. In winter he would don a quilted jacket, lined Barbour jacket, or a camelhair overcoat. His predilection for brown brogues was notable. On visiting his cottage, where he lived with his wife, a lovely woman of Italian extraction, I was surprised to find he had in his collection twenty or thirty pairs of brogues, of different qualities and in various states of repair. He explained to me the history of the brogue, the proper way to care for new brogues, and how to pair them with other items of clothing. When I think of Mr. Regelous now, I picture him sitting at the table, glass of claret in hand, going over in considerable detail the virtues of the semi-brogue in relation to the full brogue.

Mr. Regelous was always well-dressed. His normal attire consisted of an immaculate tweed jacket, checked shirt, knit tie, and flannels or cords. In winter he would don a quilted jacket, lined Barbour jacket, or a camelhair overcoat. His predilection for brown brogues was notable. On visiting his cottage, where he lived with his wife, a lovely woman of Italian extraction, I was surprised to find he had in his collection twenty or thirty pairs of brogues, of different qualities and in various states of repair. He explained to me the history of the brogue, the proper way to care for new brogues, and how to pair them with other items of clothing. When I think of Mr. Regelous now, I picture him sitting at the table, glass of claret in hand, going over in considerable detail the virtues of the semi-brogue in relation to the full brogue.  Those early lessons were not lost on me. Today I am known for my brogues; they are my signature footwear. With Mr. Regelous, discussing fine clothes, and English shoes in particular, was an education in itself, and one for which I am extremely grateful.

Those early lessons were not lost on me. Today I am known for my brogues; they are my signature footwear. With Mr. Regelous, discussing fine clothes, and English shoes in particular, was an education in itself, and one for which I am extremely grateful.