‘Won’t you dine with me?’

‘Yes. Where?’

‘I usually go to Ciro’s.’

‘Why not Paillard’s?’

‘Never heard of it. I’m paying you know.’

‘I know you are. Let me order dinner.’

‘Well, all right. What’s the place again?’ I wrote it down for him. ‘Is it the sort of place you see native life?’

‘Yes, you might call it that.’

‘Well it’ll be an experience. Order something good.’

‘That’s my intention.’

I was there twenty minutes before Rex. If I had to spend an evening with him, it should, at any rate, be my own way. I remember the dinner well – soup oseille, a sole quite simply cooked in white-wine sauce, a caneton à la presse, a lemon soufflé.

At the last minute, fearing that the whole thing was too simple for Rex, I added caviar aux blinis. And for wine I let him give me a bottle of 1906 Montrachet, then at its prime, and, with the duck, a Clos de Bèze of 1904.

Living in France was easy then; with the exchange rate as it was, my allowance went a long way and I did not live frugally. It was very seldom, however, that I had a dinner like this, and I felt well disposed to Rex, when at last he arrived and gave up his hat and coat with the air of not expecting to see them again. He looked round the sombre little place with suspicion as though hoping to see apaches or a drinking party of students. All he saw were four senators with napkins tucked under their beards eating in absolute silence. I could imagine him telling his commercial friends later: ‘…interesting fellow I know; an art student living in Paris. Took me to a funny little restaurant – sort of place you’d pass without looking at – where there was some of the best food I ever ate. There were half a dozen senators there, too,which shows you it was the right kind of place. Wasn’t at al cheap either.

‘Any sign of Sebastian? He asked.

‘There won’t be,” I said, ‘until he needs money.’

‘It’s a bit thick, going off like that. I was rather hoping that if I made a good job of him, it might do me a bit of good in another direction.’

He plainly wished to talk of his own affairs; they could wait, I thought, for the hour of tolerance and repletion, for the cognac; they could wait until the attention was blunted and one could listen with half the mind only; now in the keen moment when the maitre d’hotel was turning the blinis over in the pan, and, in the background, twohumbler men were preparing the press, we would talk of myself.

‘Did you stay long at Brideshead? Was my name mentioned after I left?’

‘Was it mentioned?I got sick of the sound of it, old boy. The Marchioness got what she called “bad conscience” about you. She piled it on pretty thick, I gather, at your last meeting.’

‘“Callously wicked”, “wantonly cruel”.’

‘Hard words.’

‘“It doesn’t matter what people call you unless they call you a pigeon pie and eat you up.”’

‘Eh?’

‘A saying.’

‘Ah.’ The cream and hot butter mingled and overflowed, separating each glaucous bead of caviar from its fellows capping it in white and gold.

‘I like a bit of chopped onion with mine,’ said Rex. ‘Chap-who-knew told me it brought out the flavour.’

‘Try it without first,’ I said. ‘And tell me more news of myself.’

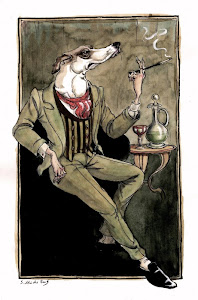

The sole was so simple and unobtrusive that Rex failed to notice it. We ate to the music of the press – the crunch of the bones, the drip of blood and marrow, the tap of the spoon basting thin slices of breast. There was a pause here of a quarter of an hour, while I drank the first glass of the Close de Béze and Rex smoked his first cigarette. He leaned back, blew a cloud of smoke across the table,and remarked, ‘You know, the food here isn’t half bad; someone ought to take up this place and make something of it.’

After the duck came a salad of watercress and chicory in a faint mist of chives. I tried to think only of the salad. I succeeded for a time thinking only of the soufflé. Then came the cognac and the proper hour for these confidences.

The cognac was not to Rex’s taste. It was clear and pale and it came to us in a bottle free from grime and Napoleonic cyphers. It was only a year or two older than Rex and lately bottled. They gave it to us in very thin tulip-shaped glasses of modest size.

‘Brandy’s one of those things I do now a bit about,’ said Rex. ‘This is a bad colour. What’s more, I can’t taste it in this thimble.’

They brought him a balloon the size of his head.He made them a warm spirit lamp. Then he rolled the splendid spirit around,buried his face in the fumes, and pronounced it the sort of stuff he put in soda at home.

So, shamefacedly, they wheeled out of its hiding place the vast and mouldy bottle they kept for people of Rex’s sort.

‘That’s the stuff,’ he said, tilting the treacly concoction till it left dark rings round the sides of the glass. ‘They’ve always got some tucked away, but they won’t bring it out unless you make a fuss. Have some.’

‘I’m quite happy with this.’

‘Well, it’s a crime to drink it, if you really don’t appreciate it.’

He lit a cigar and sat back at peace with the world; I, too, was at peace in another world to his. We were both happy.

-- Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited

08 March 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Wonderful, Codders. Thanks for reminding me of better times.

dE

Such a great text and series, always enjoyable! I listened to Gen X on your play list (100 punks) bringing back the memory of me in college almost being crushed to death via morning lightheaded math (missed addition) by the barbell I did bench presses with. Death by Billy Idol, and too many wagon wheels.

I'm slowly getting through this book when I'm not reading LSAT texts. It's such an incredibly deep novel, I love it. I'm actually reading it thanks to you mentioning it a while back, prompting me to purchase a copy.

Post a Comment